Choice on trial

The Axiom of Choice is one of the most intriguing concepts in set theory, and it has been the subject of much debate since its introduction by Ernst Zermelo in 1904. However this axiom, actually reflecting only a small part of possible choice principles, has led to some fascinating and sometimes counterintuitive results. In this blog post, we will explore some of the paradoxes that arise from the Axiom of Choice, as well as the deeper reasons behind them. We will then examine the proof that the axiom is independent from the Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory and explore the deep intuition behind it.

I try to be as informal as possible here by just delivering the abstract intuitive idea, following the principle my professor once stated: “It matters only about the proof idea. The actual proof then can be carried out in a few afternoons”. But lets begin.

At its core, the Axiom of Choice, often abbreviated with AC, seems simple enough. It states that for every family of sets \( \mathcal{F}=\{A, B, \dots\} \) with \(\emptyset \notin \mathcal{F}\) there exists a function \(f: \mathcal{F} \rightarrow \bigcup \mathcal{F}\) such that \(\forall x \in \mathcal{F} \ f(x) \in x\).

The function guaranteed by this axiom thus can be viewed as generating a set of representatives, one for each member in the family of sets \(\mathcal{F}\). The first thing one might come to mind is why this is actually an axiom as its statement seems sort of trivial. Why shouldn't a family of sets have a choice function? Is it really natural to assume that every set has a choice function? And what counterintuitive results might appear when assuming it?

These are exactly the questions we are going to tackle in this post. But lets start by explaining what I mean by choice paradoxes and have a look at an interesting paradox in classical logic:

Prisoners

Consider the following problem: There are countably infinite many prisoners standing in a row, each of them only able to look in the direction of his infinitly many successors but not behind his back (to his finitly many predecessors). Every prisoner wears a hat which is colored either blue or red. However no prisoner can observe his own hat color. The prisoners now play a game such that, starting from the first one, each prisoner has to guess his hat color. If his guess is incorrect, he dies. Before the prisoners receive their hats, they can meet and discuss a strategy for the guessing game. After the game started, they aren’t allowed to talk anymore. The question now is: Can the prisoners come up with a strategy such that independently of the hat colors, only finitly many prisoners die?

Intuitively we would expect that such strategy is impossible. Every hat color is independent from all others such that a prisoner has no better prediction strategy as just randomly guessing. So about half of of them, thus at least infinitly many ones should die.

Strangly, our intution fails us here. The answer to this problem is yes even though the deep reason behind this fact is far from obvious. The construction of the strategy goes as follows: The sequence of hat colors can be uniquely indentified by an infinite bit string (an infinite sequence of 0's and 1's). When a hat is red we substitute it with a 0 and when its blue we replace it with a 1. So we now have an infinite set of countably infinite bitstrings \(A=\{0, 1\}^\infty\) each identifying a particular game. We then construct a seemlingly complicated set (the complexity of this set is the key of the paradox here): We define an equivalence relation \(\thicksim\) on \(A\) such that \(x \thicksim y\) for \(x, y \in A\) if and only if \(x\) and \(y\) only differ in finitly many positions, i.e. the hat colors in their respective games are almost the same but differ only in finitly many hats. Given this equivalence relation we can easily define the set of equivalence classes \(A\textbackslash\thicksim\). Now entering the key part: For each equivalence class in \(A\), assuming the axiom of choice, there exists a unique representative \(x\). So each equivalence class can be identified by its representative.

Think about what we have done here: We collapsed the whole space of games into "almost similar" ones. For each of these collapses we can find a representative identifying the similarity information. So all games in a similarity class can be somehow reduced to this representative.

The strategy of the prisoners is to exactly construct this representative system we have outlined here. When the game starts, each prisoner can see only his inifinitly many successors, but his finitly many predecessors are hidden. But every prisoner knows exactly in which equivalence class the current game is: He has the inifinite amout of information to decide this (only finitly many information is hidden from him). So he also knows the unique representative of the current equivalence class. He thus guesses his hat color as if the current game was exaclty the one identified by the representative. By definition of our equivalence relation (\thicksim) the representative and the actual game only differs in finitly many places. Therefore at most finitly many prisoners guess their color wrong such that independently of the intial hat coloring this is a valid strategy.

Think about this construction and its deeper reasons. Where exactly does the paradox arise?

We now could ask ourselfs: Why do we actually need such assumption anyway? And how do these sets without a choice function look like? What makes them so special?

To answer these questions we will proceed to discuss and examine a model where AC holds and one where it fails.

Choice in the Goedel Model

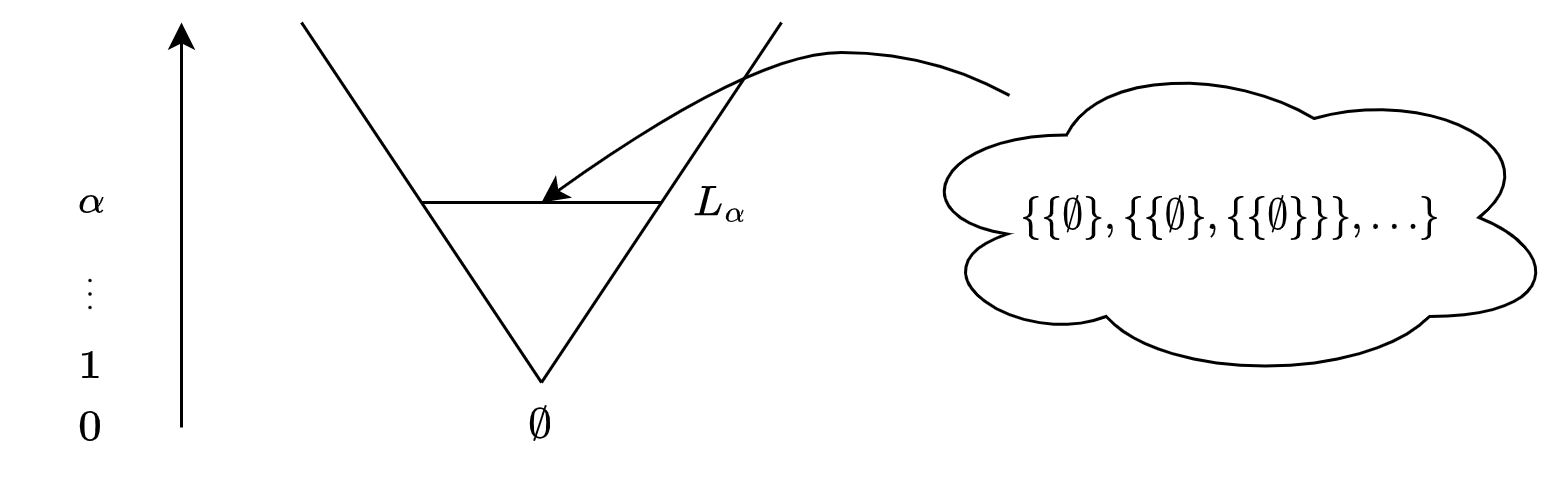

When speacking about Intuition in models of set theory, there is no way around Goedels Constructible Universe. Eventhough being a supporter of the multiverse theory of models, in my view the constructible universe is sense “mosthe in somet rational” one, as it only contains sets that are actually mathematically definable. The construction of this model is pretty straightforward: We just can build it up in a cummulative hirarchy, as we have done it for the model V. That is, we define a base case and by an inductive defintiion build more and more sets. The formal process goes like this:

- Start with the empty set as base case \(L_0 = \emptyset\)

- For each non-limit ordinal \(\alpha\) define \(L_{\alpha + 1}=Definable(L_{\alpha})\)

- For each limit ordinal \(\lambda\) let \(L_{\lambda}=\Cup_{\alpha < \lambda} L_{\alpha}\)

The \(Definable(A)\) operator is here defined as the collection of all sets that are mathematically definable with subsets of \(A\). If you are interested in the details just look it up in some Textbook. Here we are only interested in its abstraction.

Visually we can view the “V-structure” of the universe, as in every stage we are able to define more sets.

By this construction we can easily prove that the axiom of choice holds trivially, i.e. without any need for assuming it. Intuitively speaking, the constructible universe is, by construction, already structured enough that we can find a well-ordering on the whole universe. I.e there exists a well-ordering \(<\) such that for all sets in the constructible universe, if \(x \neq y\) then either \(x < y\) or \(y < x\) and every collection of sets in \(L\) has a \(<\)-minimal set.

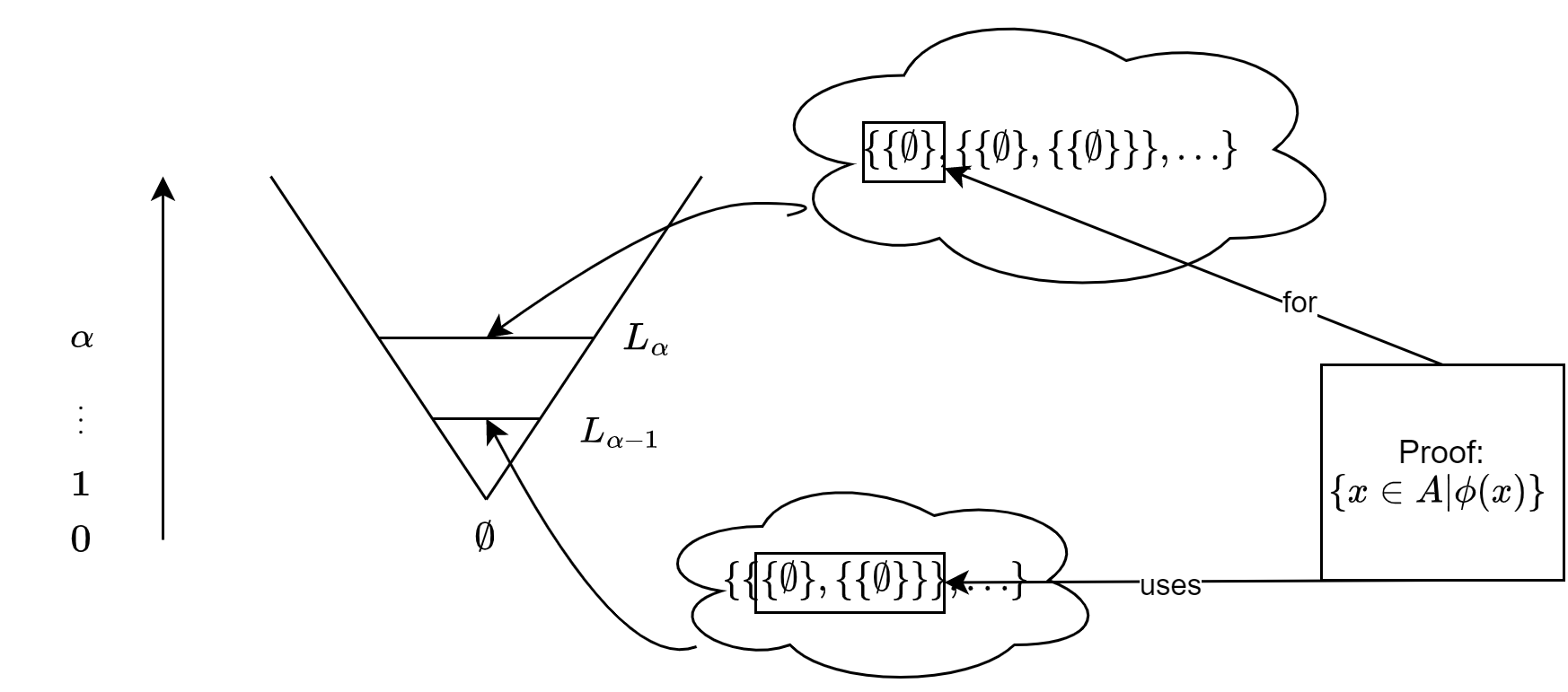

The reason of this the well-ordering is as follows:

Obviously if \(x\) and \(y\) were constructed in different stages, i.e. \(x \in L_{\alpha}\) and \(y \in L_{\beta}\) with \(\alpha \neq \beta\), then just take as minimal set the one constructed earlier, i.e. assuiming \(\alpha < \beta\) in the ordinal-relation follows \(x < y\).

So assume that \(x\) and \(y\) were constructed in the same stage. To be somewhat precise we introduce a little induction here. So let \(x, y \in L{\alpha}\) and assume that all sets in previous stages \(L_{\gamma}\) for all \(\gamma < \alpha\) are already well-ordered. Now observe that all sets in \(L{\alpha}\) have, by definition, an associated proof. We know that this proof consists of pure logical syntax and other sets as generic parameters. Since the proof is finite, the syntax part can easily be well-ordered by some lexographic ordering on the symbols of the syntax alphabet. And since the paremters are, also by defintion, only be allowed to come from previous stages thus, assuming the induction hypothesis, are already well ordered, we can merge the syntax and parameter part into a well-ordering of the complete proof and therefore also for the sets \(x\) and \(y\).

This is visualized in the following diagram:

Since we now have a universe-wide well ordering, it is easy to construct a representative function for every set. Just always take the minimal element regarding our well-ordering.

But what happened here on an abstract level? As we have seen, the constructible universe already has in some sense so much structure that we don’t have to assume any additional one. Every pair of sets can be distinguished from each other since every set has an abstract meta-concept, a construction proof associated to it. So we again see the connection between structure and choice.

Now that we understood a model in which AC holds trivially, let us have a look at a more complicated model where AC fails.

Models of ZF in which AC fails

Having seen the construction in the previous paragraoh and knowing about the connection of choice and structure, we would now expect a model with little structure, maybe also in some sense undistinguishable objects. Hardly surprising, this is exactly what we are going to construct now: There is also a famous intuition about choice principles formulated by Bertrand Russel himself. Paraphrased it goes like this: "Choosing from a set of shoes is easy. But not from a set of socks". What he means by this is that we can easily distinguish a left shoe from a right shoe. Their inherent property makes them differentiable: When observing a pair of shoes we just can choose the left or the right one. But in the socks case this argumentation somehow fails. Without making any assumptions about the shape, labeling or location of two socks, there is no way to distinguish them from each other. In this case choosing a representative is no more trivial. So Russell's intuition about choice principles highlights a fundamental concept in choice principles which we already had a glimpse at: the notion of distinguishability. It's easy to distinguish one shoe from another, but not so much for socks and exactly this lack of distinguishability is what makes choosing a representative from a collection of socks challenging.But how should we translate this informal notion into set theoretic formalism? After all, the axioms of ZF require sets to be distinguished at least in the \(=\) sense, i.e. by axiom of extensionality each differentiable \(x \neq y\) contain different elements.

The key insight here is a very generic one and absurdly deep one: We don't need sets to be distinguishable for us. We are some kind of meta-creatures, able to argue over models from a bird view. It sufficies that persons who completly "live" in the model, i.e. their perception only lies within the model borders, can't hold these sets apart. So what we want to do is to construct a model where its indestinguishable sets behave very similar in set theoretic sense. More formally: Whenever we want \(x, y\) to be in some sense indestinguishable within the model, we cram some bijections mapping \(x\) to \(y\) into it, making \(x\) seem to behave exactly like \(y\) up to this isomorphism. Nevertheless, for the contruction we actually make some kind of minor logical fraud here. We are not actually going to construct a model of ZF but for another, very closely related theory called ZFA. The trick then is that we can simulate models of ZFA by models of ZF such that if there exists some model of ZFA there exists a similar behaving model of ZF. This simluation is not relevant here. We will soon have an intution that ZFA and ZF is almost the same thing. But what actually is ZFA an why do we even need to alter our axioms?

Introducing atoms

The key idea behind indestinguishable objects is to introduce some new “ground elements”, similar to the empty set. They don’t contain any elements and are different from each other. But they are not the empty set! Because of these properties we call them atoms. Here is where the name comes from: ZF+Atoms. However knowing the axioms of ZF, one directly sees that this adjungation is not trivially possible. Consider the axiom of the extensionality: $$\forall x \forall y (\forall z (z \in x \leftrightarrow z \in y) \rightarrow x = y)$$ Since atoms don’t contain any elements this would follow that each of them is actually the empty set. So we have to make some adjustments here: First of all we introduce an axiom guaranteeing the existence of our atoms: $$\forall x (x \in A \leftrightarrow (x \neq \emptyset \wegde \not\exists z (z \in x)))$$ Secondly we alter the axioms of empty set and extensionality to prevent our atoms from collapsing into the empty set: $$\exists x (x \notin A \wedge \forall z (z \notin x))$$ $$\forall x\forall y ((x \notin A \wedge y \notin A) \rightarrow (\forall z(z \in x \leftrightarrow z \in y) \rightarrow x=y))$$

So how do our atoms actually look like? This is not relevant here. We could give a very deep construction of them using self-referential arguments, but this discussion is outside of the scope of this post. Just think of them like abstract object we just assumed to exists.

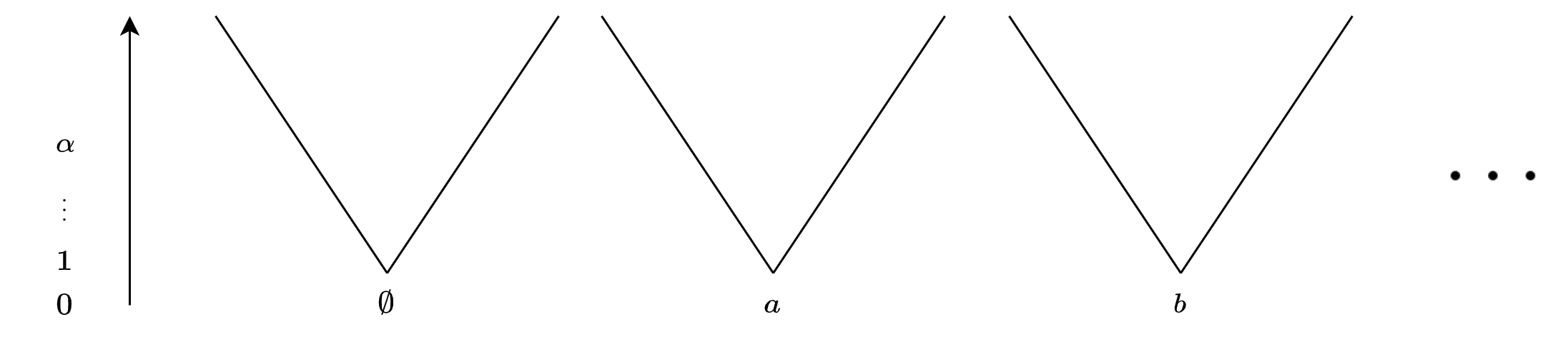

Permutation models

So now that we have our atom-enriched theory ZFA we are ready to construct a model for it. You can view models of ZFA similarily to models of ZF just that we have more base cases than the empty set. I.e. we can construct a cummulative hirarchy just as we did for the constructible universe, but starting with \(|A|\) many base cases. Visually, our cummulative hirarchy would look like this:

The second Fraenkel Model

We now finally turn to the main part of this article. Showing how choice fails in our permutation model. For this lets start out with the following atoms: $$A=\{a_0, b_0, a_1, b_1, \dots\} = \{a_i| i \in \omega\} \cup \{b_i| i \in \omega\}$$. Then construct the permutation model out of these base case atoms as outlined in the previous paragraph. We now have a model that only contains sets of the cummulative hirarchy that are symmetric up to finitly many fixes. We now claim: The set $$S = \{\{a_0, b_0\}, \{a_1, b_1\}, \dots\} = \{\{a_i, b_i\} | i \in \omega\}$$ has no choice function. First we have to make sure that the set \(S\) itself is actually in our filtered model. We have to show that \(S\) has finite support. Having understood the construction of our model this is a trivial fact. A choice function on \(S\) would for example look like $$\{\{\{a_0, b_0\}, a_0\}, \{\{a_1, b_1\}, a_1\}, \dots\}$$ but we see that to make, for example \(\{\{a_0, b_0\}, a_0\}\) symmetric we have to fix \(a_0\). Generalizing this, each atom choosen by the choice function would need to be fixed in order for the choice function itself to be symmetric. But because of our construction of \(S\) this must be done infinitly many often such that any choice function on \(S\) does not have finite support. Thus \(S\) has no choice function in this permutation model. This might not seem really mindblowing at first. But consider the implications of this:Summary

Now just take a step back and observe what we have constructed here. To destroy our notion of choice we had to destroy the well-structure of our model itself. We created a permutation model that is able to see its own automorphism. This models then contained in some sense amourphous sets which are stable under specific permutations and thus are not distinguishabe from each other within the model. So its just not that easy to go around paradoxes. This is permutations model is a pretty chaotic and unstructured place.

In the next articles we are going to dive deeper into the philosophy of choice principles and its actual core principle: Argumentation over transcendental structures.